ACCUMULATION, DISPOSSESSION AND MAPUCHE RESISTANCE: TERRITORIAL RECOVERIES IN THE FACE OF THE PANDEMIC CRISIS

BY EDGARS MARTÍNEZ NAVARRETE, NATASHA OLIVERA Y JULIO PARRA[1] Translation: Claudio Ekdahl

The pandemic crisis has had a violent impact on the ways of life of indigenous peoples in Chile and in the world, deepening their structural inequalities and exposing the colonial vulnerability to which they have historically been subjected. The Mapuche communities in resistance have faced this situation by recovering the ancestral territory that they have been deprived of and denouncing that Covid-19 is a manifestation of capitalist harmfulness to nature. However, the racist response of the Chilean State, even during the pandemic, has been to repress, persecute and criminalize anyone who opposes the interests of the ruling classes.

In Chile, the Covid-19 pandemic suspended the most important political conjunction since the end of the dictatorship. As of October 18, 2019, millions of people occupied the streets and territories of the Latin American “neoliberal oasis” seeking to change a constitutional order that has perpetuated the imperialist interests of the ruling classes. The “Chilean miracle”, as the economist Milton Friedman called the economic liberalization reforms adopted during the military regime, soon consecrated social inequality as a divine norm and the elites as its priests. In this way, the pandemic crisis that plagues the world was superimposed over the crisis of the neoliberal model, exposing its true engine: the total commercialization of social life.

In both scenarios, before and during the pandemic, the crisis management logic operated under the same punitive and impoverishing pattern: in the first, with great pain for the popular camp, leaving thousands of injured, 32 dead at the hands of the police or military and more than 2,500 political prisoners and, in the second, failing to protect the large masses of workers, saving private companies with public funds and again, deploying to the streets, numerous military troops to safeguard a useless night curfew. In this way, the process of imbrication of the coronavirus crisis is being used to articulate social control measures, precarization policies, and a set of laws for the benefit of the elites and financial capital.

Although this new pandemic context has been a lifeline for the government of Sebastián Piñera, whom after the October rebellion remained in the presidency with only 6% approval and in the sights of international Human Rights organizations, during the last recent weeks, hunger and the lack of economic opportunities have forced the popular classes to generate alternatives to feed themselves, emerging instances such as the “common pots [community soup kitchens]”. Faced with this scenario, demonstrations of rebellious indignation have sprung up again. Everything indicates that, if this complex situation continues, the popular-community rebellion will once again take to the streets of Chile with or without a pandemic.

However, this overlapping crisis has not affected the entire country across the board. As always, it is on the popular sectors and indigenous peoples where the worst consequences fall, making visible the historical accumulation of inequalities to which they have been subjected. This is why in various areas of the Wallmapu (Mapuche nation), the Mapuche communities took measures in the face of the onset of the pandemic: food support networks were activated and, in the face of the government’s null reaction, community hygiene check points were erected in order to restrict the transit of tourists and commercial transport through the territories.

“It is on the popular sectors and indigenous peoples where the worst consequences fall, making visible the historical accumulation of inequalities to which they have been subjected.”

The pandemic also exhibited certain important distinctions between the Mapuche movement and the Chilean movement, which had been “blurring” since the October uprising. Highlighting these distinctions, without the spirit of essentialist divisiveness, allows us to understand the strength contained in two ways of struggle that, beyond their particularities, identify a shared enemy. Thus, it would be impossible to establish that both collectives, after the rebellion, shared strategies of struggle.

Although they carried out joint resistance practices, which we could call a “plurinational rebellion”, these demonstrations did not manage to go beyond the immediate and symbolic levels: the massive presence of the wenufoye (Mapuche flag) in the marches, the destruction of various colonial statues in the main cities of Chile and the unstable legitimation of political violence in the hands of the famous “first line” were concrete expressions of a common affiliation that did not and has not succeeded in forging an alliance of emancipation.

In this way, although on a strategic level some Mapuche leaders recognized that their liberation as a people depended on the liberation of the oppressed Chilean sectors, the Mapuche autonomist movement marked a tactic at its own pace within the October rebellion and also within the pandemic crisis. In our consideration, this is due to a differentiated conception about the ways of understanding the historical plots of domination and emancipation that, although they are not antagonistic, contain important nuances. An example of this is how the Mapuche people, unlike the Chilean people, understand and analyze the current pandemic from the integrality of its history of submission and resistance and not as an irregular event.

The pandemic and the kuxan (disease) from the Mapuche viewpoint

The Mapuche people have been denouncing the harmfulness of the capitalist model in its neoliberal mode for decades. Not only on a material level, where the consequences of dispossession from their lands are alarming, but also around the different spiritual, cultural and political relationships that sustain their way of life and that the colonial logic of capitalism has historically stifled. Such attacks have caused multiple transformations on the territory and in the forms of human connections that develop in it, forcing local populations to disrupt production cycles, to face droughts, plagues, diseases and other adversities derived from the expansion of the forestry, energy and mining models in the Wallmapu.

In addition to this, in order to protect the interests of capital, a large part of the territory in conflict is militarized, before which the communities must deal with systematic raids, checkpoints and a series of recurrent harassments. Therefore, it is not strange that from the Mapuche cosmogony they refer to the current pandemic claiming the memory of dispossession and violence, which goes back to other evils that still affect their itrofil mongen (life in its fullness).

From the Mapuche rakizuam (Mapuche thought), it is impossible to see the current pandemic as a solely biomedical phenomenon, detached from other factors that have long harmed the totality of coexisting beings on the mapu (land). According to the Mapuche intellectual and kimche José Quidel: “The kuxan (disease) is a living entity that has various origins and that at some point manages to penetrate some of the dimensions of the che (person); It can be in his püjü (spirit), in his rakizuam (thought), in ragi chegen (the social) or in his kalül (biological body) and from there it is nourished, strengthened ”. If it is not treated, over time this kuxan will take over the framework where it was introduced, causing damage and disorders that become irremediable. This is the reason why many communities understand and explain their individual and community problems by addressing the instabilities that socially, a kuxan can cause.

“The Mapuche people understand Covid-19 as a kuxan that roots its multidimensional nature in the harmful result of a series of processes executed by capitalist and colonial devices on bodies, territories, resources and spiritualities.”

Under this conception, which challenges the hegemonic biomedical paradigm, the Mapuche people understand Covid-19 as a kuxan that roots its multidimensional nature in the harmful result of a series of processes executed by capitalist and colonial devices on bodies, territories, resources and spiritualities of Mapuche and non-Mapuche people in the long term. In other words, the appearance of this disease, which has exposed the limits of the neoliberal administration of life worldwide, is not the product of an isolated “event”, but of the harmful contemporary condensation with which the system of domination has historically developed over the Wallmapu.

Therefore, from this historical and interdependent plane derived from the Mapuche rakizuam, we could argue that the rise in Mapuche territorial recoveries in recent years is due to the need to seek alternatives for life in the face of these multiple crises that undermined their possibilities of communitarian reproduction, today again threatened by Covid-19.

The Lov Elicura as an antagonistic experience to the historical kuxanes

At dawn on January 29, more than a hundred police officers violently raided five homes in the Elicura Valley, located in Lavkenmapu (coastal territory of the Mapuche nation). Between blows, struggles and multiple violations against their families, Matías Leviqueo, Eliseo Reiman, Guillermo Camus, Esteban Huichacura, Carlos Huichacura and Manuel Huichacura were taken as detainees. Under the alleged participation in the death of a neighbor in the area, that same afternoon all the defendants went to detention control and were placed in preventive detention. At the formalization hearing, it was found that the only evidence against the community members was statements provided by protected witnesses who, in addition to being contradictory to each other, failed to establish any evidence that linked the accused to the alleged crime. Ignoring these legal gaps, the community members of Elicura were transferred to the Lebu prison (a nearby town), thus initiating their political prison that lasts until the current pandemic crisis.

Unfortunately, such an exercise in criminalization is nothing new in the Lavkenmapu. Faced with the rise of territorial recoveries or Lov (a historical and traditional form of Mapuche organization) in recent years, the State, forestry companies, and landowners in the region have used various coercion mechanisms (such as frame-ups or vitiated lawsuits) to protect the Mapuche lands that they usurped and the economic interests that they materialized on them, taking advantage of the inequalities and violations that they themselves created at the cost of community division, family impoverishment and the scarce generation of super-exploiting employment options. This set of practices constitute concrete expressions of structural violence that allow the different kuxanes to flow over the territory.

The political prisoners of Elicura are a consequence of this story. Particularly those members of the Lov Elicura, Lavkenche experience of resistance that recovered the former Las Vertientes farm two years ago, until then in the hands of the large landowners in this area: the Rivas family. This family clan settled along with other groups of settlers at the end of the 19th century on the shores of Lake Lanalhue, a sacred body of water in the Mapuche cosmogony, and since then a large part of their heirs have been responsible and accomplices of a series of dispossessions over the Elicura Valley, racially subduing its population and systematically commodifying its natural resources.

Starting in the last century, a profoundly unequal land concentration process for local populations began. Although there were substantial advances in favor of the communities during the Agrarian Reform cycles (1962-1973), these were severely interrupted by the coup d’état, an event used by many wealthy families in the area, including the Rivas, to expand their territorial demarcation acquiring properties and parcels under illegal methods or at ridiculously low prices. Through the agrarian counter-reform in the Elicura Valley, the portions of land that did not continue in the hands of large landholders, the State ended up fragmenting them through two main routes. On the one hand, the land located in wooded areas were acquired by forestry entrepreneurs through dubious auctions, which allowed them a rapid expansion of the monoculture of pine and eucalyptus supported by generous state grants. On the other hand, the widest hectares of the fertile valley was handed over to Chilean landowners, cornering the Mapuche families in small farms in which it was impossible for them to carry out their subsistence activities, mutilating their productive dynamics, harassing their cultural practices, and forcing them to live under the dependence of business owners.

Miguel Leviqueo Catrileo, a resident of Elicura, expresses: “We Mapuche always live in small pieces of land while the rich made their houses on hilltops, in tremendous plots, from there they looked at us as we sowed the little we could to live on.” These processes, aimed at dismantling the Lavkenche communities, continued under other modalities once the dictatorship ended. The Rivas, as the “owners” of the Valley, filled their pockets with the forestry business and formed alliances with the large timber capital, jointly expanding the monoculture plantations that by then already surrounded the Elicura Valley. Despite the political conquests that the Mapuche movement managed to establish during the neoliberal period and certain legal openings that allowed their presence in restricted democratic spaces, the multicultural logic of capitalism in the transition perpetuated dispossession throughout the Wallmapu.

In this context, the profound conditions of inequality in which the Lavkenche families of the Valley lived, became more acute again with the arrival of different transnational companies at the beginning of this century. First, some minor aggregate extraction companies attacked the Calebu and Elicura rivers, the main water arteries in the territory that feed Lake Lanalhue, causing irreparable damage to them. Subsequently, since 2016, with the approval to build the “Gustavito” hydroelectric plant by the Spanish energy corporation Hidrowatt, which belongs to the Impulso business group, the plans to build two other hydroelectric plants in the Valley by this economic conglomerate were evidenced. Faced with such a situation, which was beginning to arouse suspicion and indignation, Lonko [community leader] Miguel Leviqueo indicated: “They do not benefit us at all, they only bring us destruction.”

Such threats quickly became common enemies for a deeply fragmented and disunited local population as a result of the multiple violence and racism to which it had been subjected for a long time. The imminent arrival of the hydroelectric plants to the territory meant a collective encounter in the face of past and present injustices, common indignation that was reflected in the words of Pamela Rayman, a member of Lov Elicura: “We are already plagued by forestry companies. With Hidrowatt it won’t be the same”. During that year the Movement in Defense of the Rivers of the Elicura Valley was born, an organization made up of Mapuche and non-Mapuche people that carried out a series of actions to stop the installation of these megaprojects, reaching its apogee in July 2016 with the blockading of the P-60-R highway that connects Cañete and Contulmo, two of the main urban centers in the area. Although this movement sowed the first seeds of collective antagonism in the Valley after long years of lethargy, the burnout from the legal struggle, the intrinsic frictions of any organization, and some conformism in the face of certain advances in the struggle ended up dissolving the movement.

But the resistance in the Elicura Valley did not end with the movement. The elikurache youth (local territorial affiliation), born and raised among pines and landowners, were not satisfied with these small victories and, affirmed in their right to self-determination, decided to advance in the territorial and cultural reconstitution of the Valley: the only possible way to tear apart the history of submission that weighed on their shoulders. In this way, on January 21, 2019, a group entered to recover the Las Vertientes Estate, which until then belonged to an heir of the Rivas family, thus creating the Lov Elicura and becoming an experience of resistance that has represented a concrete obstacle to the advance of the plunder in the Lavkenmapu. Since then, the Chilean structures of domination have deployed various repression mechanisms over this Lov, trying to dismantle the activities that sustain their community fabric and with which the awareness of those people who still do not dare to confront them is possible. The raid that occurred at the end of January and the subsequent political imprisonment experienced by the members of this process should be seen as one more action in this strategy of persecution and harassment.

The Mapuche Political Prison in Times of Pandemic Crisis

“We are in times of struggle, but also of resistance. We must support each other as brothers and sisters in any territory and speak out against threats of any kind. Leave passivity and take action. This strike is that, it is a step towards mobilization since it is preferable to die fighting than on our knees before an oppressive system that through fear of a virus it relentlessly subdues”, says Machi Celestino Córdova from his hunger strike in prison in Temuco.

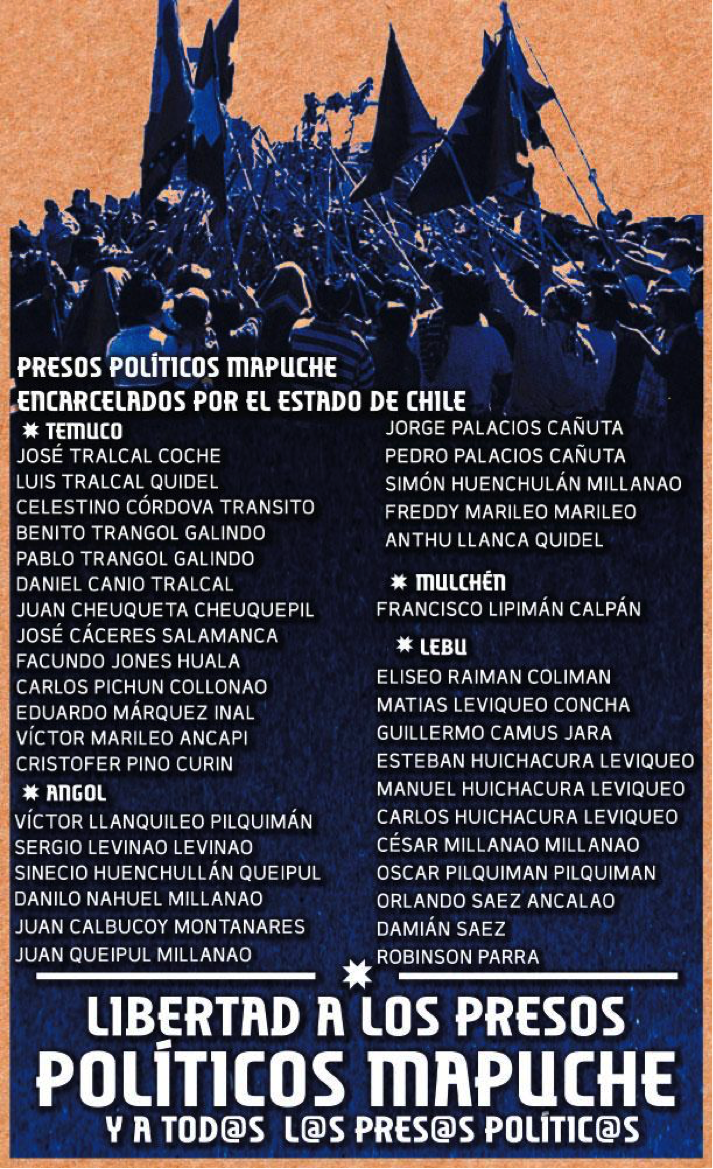

On February 11, 2020, different Lov and resistance communities from Lavkenmapu and other territories met outside the Lebu prison in order to support the political prisoners of Elicura who had already served a dozen days behind bars. Through a statement that was made public, they thanked all the people who accompanied them that day in the performance of a nguillanmawün, a Mapuche ceremony aimed at providing them with newen (strength) and demanding justice in the face of the process that keeps them deprived of their freedom. In addition, they reiterated their support for all Mapuche and non-Mapuche political prisoners held in different prisons in Chile. To date, there are more than 30 Mapuche who are in preventive prison or serving sentences for different reasons, forced to live the pandemic in drastic hygienic conditions typical of confinement. Such a situation, in addition to violating their Human Rights, violates the principles of Mapuche medicine that establish a close link between the che (person) and the different activities carried out in their mapu (territory). Likewise, given the worsening of punitive state measures, some gray areas have proliferated within prisons that are used by gendarmerie personnel to exercise different forms of racist violence against the Mapuche population.

Faced with these clear disadvantages experienced by Mapuche political prisoners before the Chilean courts, since Monday, May 4, many of them held in jails in the cities of Temuco and Angol made the drastic decision to start or resume a hunger strike as a pressure measure before the executive and judicial system. With this harmful to themselves determination, which continues to this day, they demand that the government adhere to ILO Convention 169 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which indicate the option of changing the precautionary measures in these crisis contexts. They also demanded the return of the usurped ancestral territory, the withdraw of the transnational companies responsible for the imbalance in Mapuche life, and the demilitarization of the Wallmapu. Lastly, they made a mobilizing call for all expressions of resistance that fight day by day for the national liberation of their people.

“They demanded the return of the usurped ancestral territory, the withdraw of the transnational companies responsible for the imbalance in Mapuche life, and the demilitarization of the Wallmapu.”

However, in a ridiculous and indifferent way to the demands of the Mapuche political prisoners, the response by the Chilean judicial system was to grant the change of precautionary measure to the police officer responsible for the death of Camilo Catrillanca in November 2018, allowing him to go through his legal process in house arrest due to the threat that Covid-19 posed to his life. Contrary to that, the courts have systematically denied changing the precautionary measures of the accused Mapuche as a result of the existing territorial conflict in Wallmapu. The criminalization in times of pandemic, the racist nature of justice, and the government’s indifference to take up the demands of Mapuche political prisoners on hunger strike; have generated a progressive increase in resistance actions in the areas of Arauco and Malleco: the epicenter of the territorial conflict between the state, forestry companies and landowners with the communities and the Mapuche in resistance. In this way, there has been a continuity in the territorial recoveries and the multiple forms of protest promoted by the contemporary Mapuche movement.

Although the political prison in Chile affects in a transversal way the communal and popular sectors that have decided to fight for a different society, the racist and colonial bias with which the judicial system operates under the economic-political interests of the State violates in a particular and situated way the Mapuche people. In this way, jail and political persecution constitute mechanisms of submission against those resistance experiences such as the Lov Elicura where Mapuche people have built, meter by meter, emancipatory alternatives of life in the face of the true kuxan that plague the world: capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy.

[1] Edgars Martínez Navarrete, Natasha Olivera and Julio Parra are members of the Mapuche media outlet Aukin. Edgars Martínez is also a doctoral student at CIESAS – CDMX. This article is in memory of Miguel Leviqueo Catrileo, the members of the Lov Elikura and all the political prisoners in Chile.