Greater Chaco Is Not for Sale! Stop Trump’s Colonial Land Grab

by The Red Nation

Trump’s war on the planet and Indigenous peoples has now turned to the San Juan Basin, the Greater Chaco Region, and its Diné residents as another national sacrifice zone in the name of profit. Aggressively expanding Obama era policies to increase domestic energy production to drill the US economy out of the Great Recession, the Trump administration has fast-tracked the approval of the Dakota Access Pipeline and the Keystone XL pipeline; has reduced the size of the Bears Ears National Monument, a sacred site to five Native nations, opening millions of acres for uranium mining; has opened billions of acres for offshore drilling; and now hopes to lease the remaining six percent of unleased lands in the Greater Chaco Landscape for fracking.

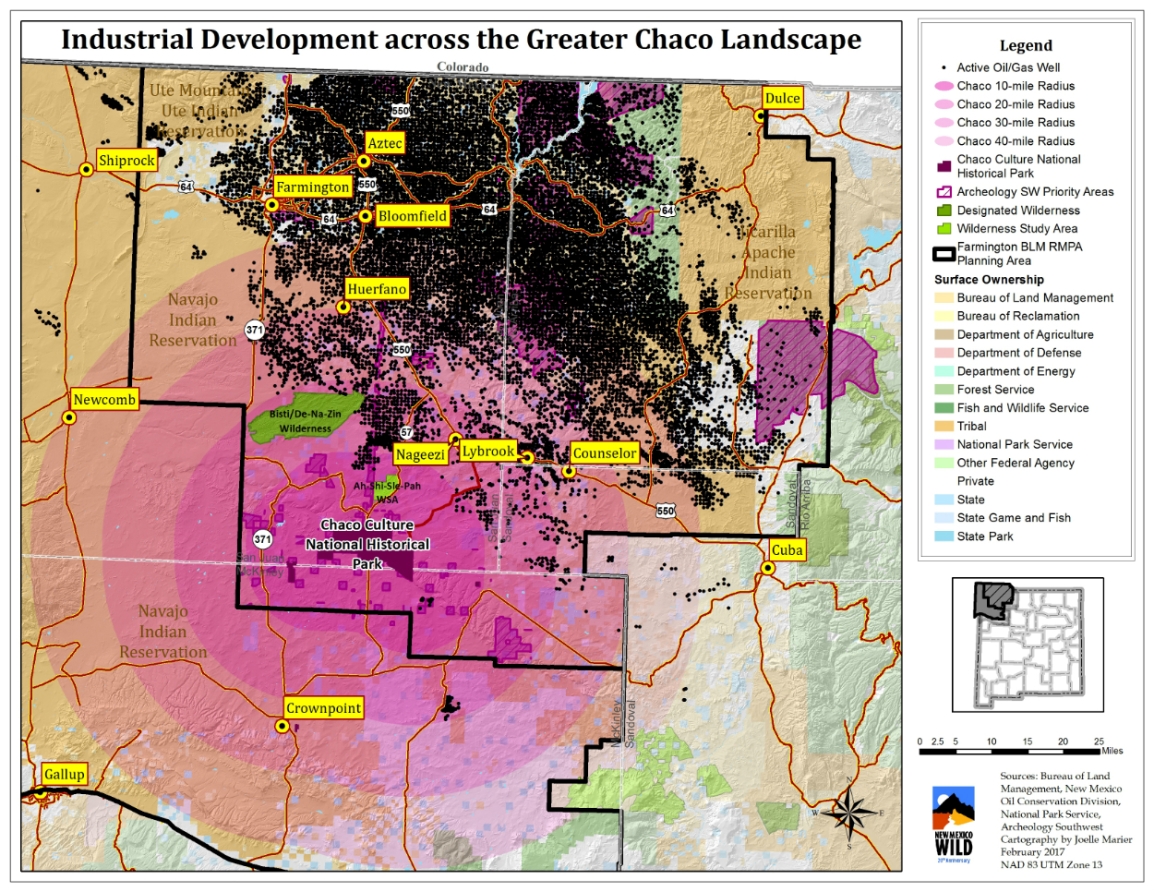

As the struggle to protect the Greater Chaco Landscape and Eastern Navajo communities intensifies, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) continues to illegally lease Indigenous lands for exploratory oil and gas drilling in the San Juan Basin. The affected Diné communities are Counselor, Huerfano Mesa, Nageezi, Twin Pines, Pueblo Pintado, Torreon, and Ojo Encino, some of the poorest places in North America. The Greater Chaco Landscape also holds immense cultural significance to the nineteen Pueblo nations of New Mexico. These areas are an origin place for Indigenous peoples throughout the Southwestern United States, as well as into Mexico and Central America. It is more than a heritage site, but an entire historical and spiritual landscape of countless ancestral and abundant cultural resources — a sacred landscape the BLM has placed on the auction block.

Currently, 94 percent of the Greater Chaco landscape has been leased for drilling. The BLM plans to lease the remaining six percent without an environmental and health impact study and free, prior, and informed consent from Diné residents, the Navajo Nation, and the nineteen Pueblos who have cultural ties to the Greater Chaco Region. Twenty-six parcels are currently slotted to be leased for oil and gas drilling. The approximately 4,800 acres of land will be auctioned online for leasing on March 8, 2018. (See planned actions for protesting the BLM auction at the end of this article.)

While there have been widespread efforts to protect Chaco Canyon, a sacred site to many Indigenous nations and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, there has been little focus on the actual Diné communities living in the Greater Chaco Region most impacted by extractive industries. More than a century of intense extraction of coal, uranium, oil, and gas in the San Juan Basin has left behind a wasteland of contaminated water, air, and soil, making some areas unfit for human and other-than-human life.

Unlike other parts of the Navajo Nation, Eastern Navajo Agency was allotted during the 1880s under the Dawes Act. Over the years, Eastern Navajo has become a “checkerboard,” a mix of Tribal, state, federal, and private lands. A region with such a complicated land ownership system is easily exploitable and is currently utilized by the BLM to undermine tribal communities opposed to fracking. Horizontal drilling on BLM leased lands tunnels directly under and thus impacts adjacent Tribal, private, and individual allotted lands without residents’ consent, bypassing mandatory community consent processes, and allowing the auctioning of leasings in a quick and silent manner.

Since 2003, the BLM has used an outdated resource management plan to continue to plunder Indigenous lands. The current plan accounts for vertical drilling but doesn’t specify new technology in hydraulic fracking, which uses horizontal drilling. It also doesn’t account for the millions of gallons of water each drill requires. Since neither hydraulic fracking nor the intensive drain on precious water resources are considered, the BLM is unable to adequately assess the environmental and health impacts of extractive operations in the Greater Chaco Landscape. Therefore, affected communities and life on the land, such as traditional medicines and herbs, have little recourse and are not informed of the health-related consequences. The effects have been devastating and nothing short of criminal.

The Counselor Chapter House, along with the Diné communities near Nageezi — Dzil Na’ohdli, Torreon, and Ojo Encino — have vigorously opposed fracking and have relentlessly voiced their concerns against the current resource management plan that does not include health or social impact statements. Each community has cited opposition to the plan for the sake of community health, public safety, and general welfare. But their concerns have gone largely unheeded by the federal government, Navajo Nation, and the state of New Mexico, who have each expressed concern over the protection of Chaco Canyon National Park, but not for the people living in the Greater Chaco Region.

Hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, is a process that involves injecting millions of gallons of water, sand, and unnamed, yet highly toxic, chemicals at high pressures to “fracture” the shale bed to release oil and gas deposits. More than 700 chemicals are used for each drill. This process frequently contaminates groundwater and underground aquifers, freshwater sources vital and scarce in high desert climates like the San Juan Basin. Groundwater contamination is often irreversible. Because the industry refuses to identify the kinds of chemicals used in the fracking process, it is hard to diagnose fracking-related illnesses caused by contaminated water systems.

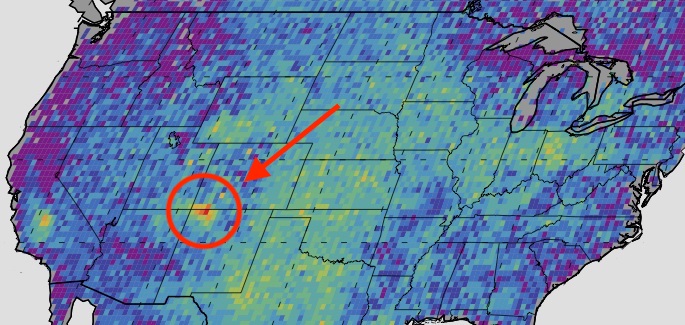

As fracking plumbs the depths of the earth, often poisoning groundwater, it also pollutes the atmosphere above it. Methane emissions, a byproduct of fracking, have created a toxic cloud so thick hovering near the Four Corners area that it was detected by NASA spacecraft. Methane, an odorless and colorless gas, is a greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide in accelerating climate change and is the second leading pollutant causing climate change. Since methane emissions can only be detected by special technology, it is near impossible to monitor the leakages from storage tanks, well pads, and processing facilities.

Diné residents living near oil and gas injection sites on BLM leased land also experience an aggravated anxiety and distress related to the unknown volatility of drilling materials stored next to housing areas. In July 2016, the explosion of thirty-six storage units containing frack and oil fluid forced fifty-five community members to flee their homes in the middle of the night. Because residents were not informed the storage tanks contained explosive chemicals, there were no emergency or public evacuation plans in place. With no recourse to hold the companies responsible for the killing of livestock and the trauma inflicted on young children, the community was left with unanswered questions and paying for the damages themselves.

There are still no evacuation plans in place and emergency response is slow to these geographically isolated communities. A checkerboard of land ownership — the multi-jurisdictional patchwork of Tribal, state, and federal jurisdictions — also makes it complicated for emergency responders, who often take hours to arrive to a scene.

Extraction exhausts already exhausted, and sometimes absent, local infrastructure, whether its access to healthcare, employment, or quality transportation. Community members have complained about increased traffic on already poorly maintained roads and the increase in violence associated with extraction. The creation of “man camps,” the temporary camps of mostly male oil and gas workers, are related to increased rates of sexual violence, human trafficking, and the rape, murder, and disappearance of Indigenous women and girls.

US highway 550, the main road cutting through the heart of the development area, is known to the local community as “the killing zone,” because of frequent and deadly traffic accidents. Big diesel trucks tear up dirt roads not meant for heavy traffic, forcing smaller cars off the road and regularly causing accidents which are sometimes fatal. Travel is precarious especially during monsoon season, when entire roads wash away or become untraversable because of mud ruts left by oil industry big rigs. In response to complaints, industry representatives tell community members to monitor truck speeds. But it’s not the community’s responsibility to make sure trucks don’t kill people.

All of the deadliest risks and costs needed to make a profit are placed onto the poorest people. When roads are destroyed, public or Tribal monies are needed to pay for their repair, which often takes years or simply never happens, making it difficult or near impossible for isolated communities to travel for basic needs such as groceries.

Fracking has also fractured community cohesion. The revenue generated by an estimated 22,000 natural gas wells pays royalties to community landowners and allottees. Leases were signed often without knowledge of the long-term and permanent destruction to the land. While some landowners collect royalties, those living next to them have no choice but to live with the consequences of fracking — methane emissions, destroyed roads, increased violence, contaminated drinking water, etc. — while not receiving a penny or consenting to fracking in the first place.

The Navajo Nation President, Russell Begaye, has stated, alongside the All Pueblo Council of Governors, that he supports the protection of Chaco Canyon National Park. Yet, the Navajo Nation is currently in a year-long discussion about whether or not fracking is good or bad for the nation. This is despite the fact that Diné communities most affected by fracking, such as in Eastern Navajo Agency and Northern Navajo Nation in Utah, have passed resolutions opposing fracking entirely. If Tribal leaders support the protection of sacred sites, why cannot they not extend the same protections to the people most affected? Diné residents have spoken and have said no to fracking. So, what is there to debate?

The widespread and historic support to protect Chaco Canyon is a welcome achievement. But as we extend protections for sacred sites, we must remember the people who live on that land. As Indigenous peoples who are made ever vulnerable by the expansive reach of extractive industries and catastrophic climate change, we are well aware that what we do to the land, we also do to our bodies. If we kill the land, we kill ourselves. Protecting Chaco Canyon is not enough if that same protection for the land is not extended to the human life on that land. After all, what’s the point of protecting sacred sites when the caretakers of those sacred sites are allowed to die? We need deeds not words.

Follow The Red Nation, Pueblo Action Alliance, Frack Off Greater Chaco, and Diné-Pueblo Solidarity for information on fighting back against fracking in the Greater Chaco Landscape.

#NoNewLeases #GreaterChacoNot4Sale

Upcoming Actions:

March 5 @ 2 PM: Bureau of Land Management Office, Farmington, New Mexico

March 7 @ 3:30 PM: Bureau of Land Management Office, Santa Fe, New Mexico