“To Keep a Place of Prayer:” Tasing is Just the Latest Incident in a Long History of Colonial Violence at Petroglyphs

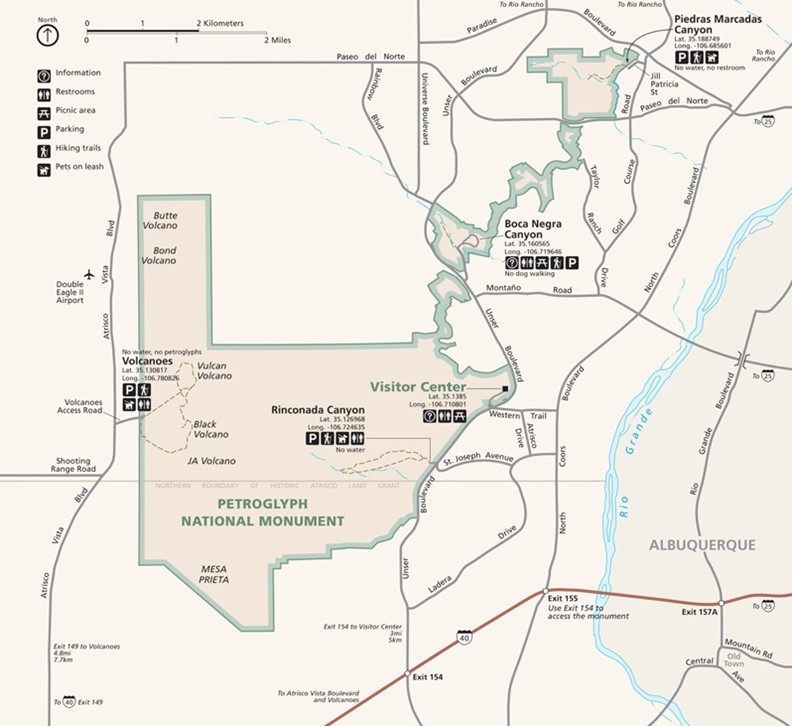

On December 27th, a National Park Service employee tased Darrall House, a Diné/Oneida man, at the base of the Petroglyph National Monument in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He went there to pray, to keep a place of prayer. He ventured off the trail to avoid a large crowd and was tased [1].

The violence captured on video shows a literal form of colonial violence against Indigenous peoples on sacred sites. Organizations like the Red Nation are calling for a full investigation of NPS actions and are demanding the land back [2]. The incident is the latest in a long history of colonial violence against Indigenous peoples at the Petroglyphs.

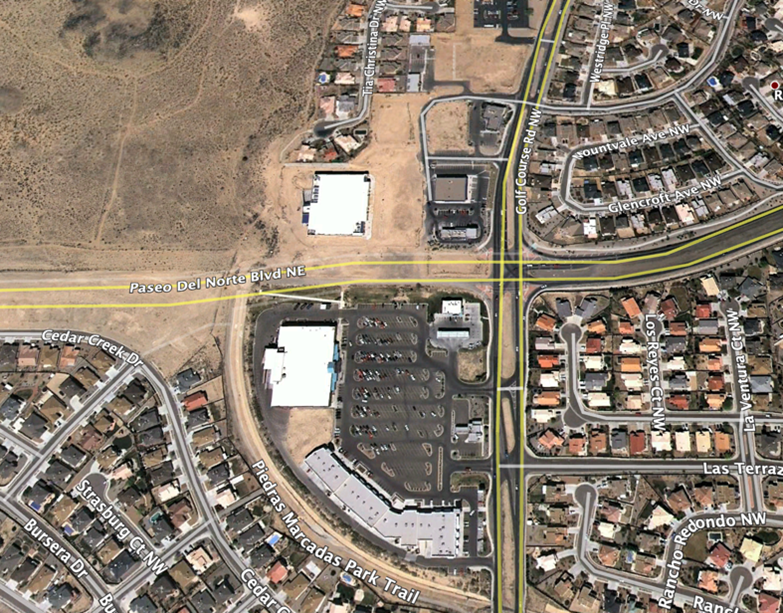

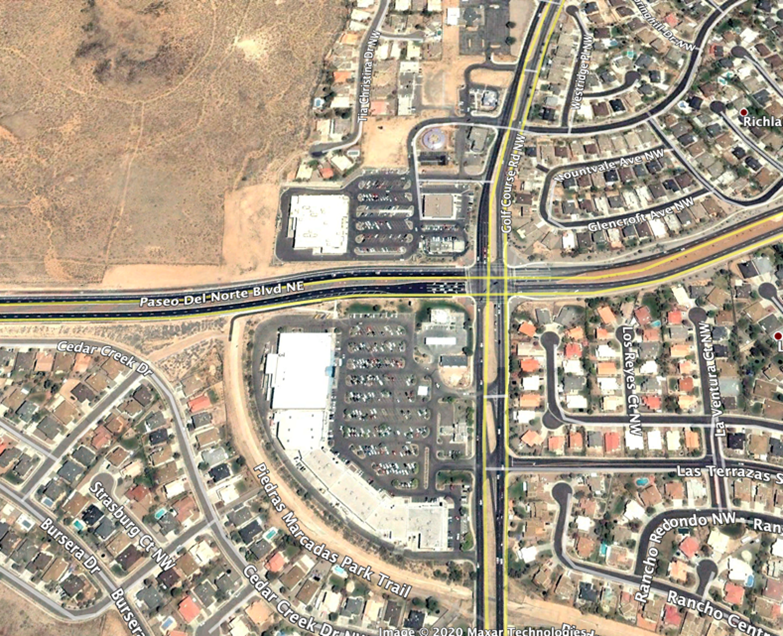

The people who actually threaten the park and damage it are never tased – these are the senators, city councilors, mayors, and real estate developers who conspired in the late 1990s and early 2000s to extend the Paseo Del Norte highway through the center of the monument.

History of land theft

Land theft at the Petroglyphs started in 1692 with the Atrisco Land Grant. Representatives of the Spanish King arbitrarily gave much of what is now the South Valley to Spanish settlers. These were the prosperous lands of the Isleta Pueblo and other Tiwa peoples along the lush banks of the Rio Grande.

The land grant was eventually expanded in the 1750s to include what is now Albuquerque’s westside [3]. During the Spanish and Mexican periods, land grants served as frontier posts for colonization. They were based on class difference and ushered in the racial divisions between Hispano, Pueblo, and other Indigenous nations that exists into today.

In its annexation of New Mexico in 1848, the United States recognized Spanish land grants. By this time, the lands evolved from subsistence use to commercial grazing for meat and wool products. This evolutionary change in land use was part of the history of capitalism in New Mexico [4].

With U.S. conquest, the nature of land laws shifted in the direction of individual property rights over collective grazing lands. In 1891, the New Mexico territorial legislature passed a law that started a process by which old Spanish land grants were converted into property rights [5]. The practice of property rights, however, didn’t take root immediately. For the next 60 years, heirs of the land grant fought each other over control of the lands.

By the 1960s, the land declined in both subsistence and commercial use. It became valuable as future urban space for an expanding Albuquerque. The fighting between descendants of the land claim led to the formation of a private corporation out of the shared land titles of the Atrisco land grant. In 1967, in a narrow vote, heirs approved the formation of the Westland Corporation, now Westland Development Corporation [6]. The corporation converted property rights into shares. The development corporation sold much of the original land grant to real estate developers, expanding Albuquerque’s westside.

In the 1980s, Indigenous leaders, conservation groups, and even some heirs to the original land grant recognized the threat of expanding housing on Albuquerque’s westside. They organized to petition city leaders and state officials to convert the land into a national park [7]. Indigenous activists and organizers formed the Petroglyph National Monument Coalition in the early 1990s. The coalition became the Sacred Alliance for Grassroots Equality (SAGE Council) that advocated for the protection of the Petroglyphs as a spiritual right for Indigenous peoples.

As the late Indigenous activist and Sage board member Rose Ebaugh said in a 2005 interview, “At first it was considered an environmental issue, but it turned into a spiritual/religious right to keep a place of prayer” [8].

In 1989 members of the Havasupai nation held a series of prayers from the Grand Canyon to the Petroglyphs. They recognized the Petroglyphs as the people’s emergence and met with heirs of the Atrisco land grant to find a way to protect the Petroglyphs [9].

Due to this pressure, the Petroglyphs were converted from a land grant into a national monument in 1990 [10]. Yet the Westland Development Corporation, representing the heirs of the Atrisco land grant, was recognized as a stakeholder in the Petroglyph National Monument Establishment Act of 1989, perpetuating the lineage of Spanish colonial rule over the interest of the Pueblo peoples [11].

For the Hispano descendants of the land grant, the land assumed an abstract character of a yearly dividend. All the while, the Pueblo nations in New Mexico and Arizona never forgot their connection to the land. Despite legal and physical barriers, the maintained all these years connection to the ancient Petroglyphs their ancestors carved in reverence to the rivers, mountains, and plains that surround the volcanic rock.

Other landowners on Albuquerque’s westside saw sacred sites became literal obstacles to profit. In the late 1990s, former cattleman turned real estate developer John Black proposed 19,000 homes west of the national monument. This project was called “Quail Ranch” [12]. Since 1972, Black made a living selling his family ranch for housing and real estate development [13]. This included much of the business activity on north Coors Blvd like the Cottonwood Mall that opened in 1996. That same year, Sandia Properties developed Ventura Ranch, west of Paradise Hills on the former Black Ranch and in the route of extended Paseo Del Norte.

The threat of urban sprawl

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the westside was in rapid expansion. Sections of the Black Ranch was converted into housing and the construction of new shopping centers like the Cottonwood Mall. Paradise Hills (including Ventura Ranch) and Taylor Ranch expanded. This created new infrastructure demands on the city, including roads. While the rest of the city, particularly neighborhoods of color, saw road maintenance fall apart and businesses close, the westside was sprawling. Pro-growth organizations financed studies that argued for more roads on the westside. Developers created a crisis, and they demanded the city solve the problem. Urban sprawl was a public cost for private profit. And fundamentally it was built on the theft of Indigenous lands – particularly the Petroglyphs.

Although an initial supporter of the national monument in 1990, in 1997 Senator Pete Domenici of New Mexico worked to reduce the park boundaries to allow for the extension of the Paseo Del Norte, a four-lane highway, through the center of it [14]. He attached a rider to a military spending bill that withdrew 8.5-acre corridor from the park and turned it over to the city.

Outgoing Mayor Martin Chavez testified during hearings in Congress in favor of the amendment and highway extension [15]. He would later offer crucial support for the project in 2003 after he returned to the mayorship following an unsuccessful campaign for governor.

In 1999 the new mayor of Albuquerque, Jim Baca, challenged the development of Black Ranch. He said it would drain Albuquerque resources in trying to meet new infrastructure obligations [16]. Smart Growth organizations like New Mexico PIRG and 1,000 Friends of New Mexico made similar arguments. Already new housing and commercial development on north Coors Blvd. required that the city to expand water, energy, roads, schools [17].

The SAGE Council mobilized against the money and power interest of the city and state. They partnered with environmental groups, local and national, to stop the road. The Albuquerque city council put the funding for the road, at and estimated 12 million dollars, in the form of a bond. Under this arrangement, the city agreed to pay for the construction of a road to nowhere that violated sacred lands in order to expand housing on the city’s westside.

During the fall semester of 2003, I spent my evenings knocking door-to-door throughout Albuquerque neighborhoods asking people to reject the bond. Although I worked as a paid canvasser for 1,000 Friends of New Mexico. I spoke with random residences in central Albuquerque on my canvassing route. I stressed the importance of the site for Indigenous peoples alongside the tax burden argument the organization wanted me to push. The city was uneven in its support/opposition of the road. The expanding westside wanted it. Most of the neglected neighborhoods in central and south Albuquerque recognized they did not benefit from the expansion of the highway and voted against it.

The city’s taxpayers were asked to shoulder the cost and for the first time in 18 years, voters rejected a city bond – defeating the “Streets Bond” that included money for the controversial project [18].

But the following year, Governor Richardson proposed $9 million in capital spending for new roads on the westside of Albuquerque – $2 million for an extension of Paseo Del Norte through the Petroglyph National Monument alone [19]! The New Mexico State Legislature eventually approved $5.4 million in state money for Albuquerque road projects, offsetting the cost for Albuquerque residents [20]. This action moved the cost of the project to a wider public, but maintained potential profit in the form of real estate development in the same hands.

On November 2, 2004, during a federal election, Albuquerque voters approved the $52 million in street bonds– thereby financing the extension of the highway and the desecration of sacred sites. Of that, $8.7 million went to the extension of Paseo Del Norte. $3.3 million in “capital outlay” funding included from Republican State Senators [21].

Indigenous activists and organizers, conservation groups, and others challenged the legality of the vote, but to no avail. Construction on the extension began immediately and by 2007 the extension through the Petroglyphs was complete [22]. As it turned out, the costly campaign created a multimillion-dollar road to of Ventura Ranch.

In 2006 the California based SunCal Companies bought the Westland Development Corporation, the former Atrisco Grant, ending 350 years of Hispanic connection with the land on Albuquerque’s westside [23]. The SunCal Companies immediately started to convert portions of the grant into housing near I-40 and Coors, south of the Petroglyph Monument – applying for city and state tax breaks along the way [24].

The proposed Quail Ranch, the project that would have brought 20,000 new homes on the west side of the Petroglyphs never materialized. In 2007 the developer ended the project, citing water concerns and SunCal’s new housing development. In the late 2007 Albuquerque’s housing sales were slumping [25]. The following year the financial housing market crashed, ushering the worst recession since the Great Depression.

Continuation of colonial violence

The shocking video showing a park ranger tasing a Native man is part of legacy of colonial land theft. It is an effect of dispossessing sacred sites from Indigenous communities for settlement expansion, extractive industries, ski resorts, or the expansion of highways. What happened in December at the Petroglyph National Park also occurred in Oak Flat in Apache lands, the Snowbowl near Flagstaff, Arizona, Bears Ears in southern Utah, and many more places.

Today, Albuquerque city councilors are again talking about expanding Paseo Del Norte. Cynthia Borrego and Ken Sanchez are proposing $24 million to expand portions of the road that go through the Petroglyphs. Studies are already on the way. Again, the justification is to ease congestion [26].

Colonial institutions, such as local and federal courts, city and county governments, the federal government, regularly disregard Indigenous appeals to protect sacred sites when profit is involved. The irony is that the park ranger justifies his attack on a Native man as protecting the park. But the park was long damaged and more substantially put at risk by the government that employees him.

References

[1] Chris Ramirez, “Video: Park ranger tases Native American man at Petroglyph National Monument,” KOB4, December 28, 2020. https://www.kob.com/albuquerque-news/video-park-ranger-tases-native-american-man-at-petroglyph-national-monument/5962472/, last accessed, 1/5/21.

[2] http://therednation.org/we-condemn-racist-national-park-service-for-brutalizing-darrel-house/.

[3] https://www.atriscoheritagefoundation.org/, last accessed 1/3/21.

[4] Ortiz, Roxanne, 2006. Roots of Resistance: A History of Land Tenure in New Mexico, University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK.

[5] John McMillion, “Former Legal Decisions Increase Old Problems of Atrisco Grant Heirs,” Albuquerque Journal, July 21, 1967, A1,A7, last accessed 1/3/21.

[6] Bill Hume, “Atrisco Land Grant Heirs Plan to Form Stock Corporation,” Albuquerque Journal, July 23, 1967: A1-A2.

[7] Ollie Reed Jr., “A monumental anniversary: A natural and cultural landmark, Petroglyph National Monument was designated 30 years ago on June 27,” Albuquerque Journal, June 26, 2020. https://www.abqjournal.com/1469879/a-monumental-anniversary.html, last accessed 1/3/20.

[8] http://newmexico.indymedia.org/uploads/2005/11/sage_council_part_1.mp3., last accessed 1/3/20.

[9] Michael Hartranft, “Rock Art Ceremony Scheduled for Monday,” Albuquerque Journal, September 30, 1989.

[10] https://www.nps.gov/petr/learn/historyculture/recent-history-of-petroglyph.htm, last accessed 1/3/21.

[11] https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/745/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22Petroglyph+National+Monument%22%5D%7D&r=2&s=3, lase accessed 1/3/21.

[12] https://sacredland.org/petroglyph-national-monument-united-states/, last accessed 1/3/21.

[13] https://wwrealty.com/john-black/, last accessed in 1/3/21.

[14] https://www.deseret.com/1998/3/16/19369170/road-through-monument-gets-panel-s-nod; https://www.deseret.com/1998/4/6/19373044/bulldozers-await-drive-through-petroglyphs, last accessed 1/3/21.

[15] Michael Turnbell, “Extension Fight Goes to D.C.,” Albuquerque Journal, October 23, 1997: A1-A2.

[16] Tania Soussan, “Mayor: West Side Expansion Premature,” Albuquerque Journal, June 18, 1999: A1-A2.

[17] Tania Soussan, “Forum Explores Black Ranch Development Plan,” Albuquerque Journal, August 20, 1998: D2.

[18]https://www.bernco.gov/uploads/FileLinks/79348cd740e345bea002a370926b6cc0/Regular_Municipal_Election_2003.pdf, last accessed 1/3/20.

[19] David Miles, “Gov. Recommends $9 million for Roads.” Westside Journal, February 10, 2004. Page 2.

[20] Jim Ludwick and Dan McKay, “NW Won’t Hog Bonds for Roads,” Albuquerque Journal, June 22, 2004: A1 and A6.

[21] Andrea Schoellkopf, “Area Groups Allowed In Paseo Suit,” Westside Journal, July 15, 2005: 1 and 2.

[22] Rory McClannahan, “Milestone for a passageway,” Albuquerque Journal, December 10, 2007: A1.

[23] Peter A. Sanchez, “Atrisco Heirs Sold the Land, Preserved the Culture,” Albuquerque Journal, December 6, 2007: A11.

[24] Marjorie Childress and Gabriel Nims, “Officials Should Check the Hidden Costs of TIFs,” Albuquerque Journal, December 2, 2007: B3.

[25] Richard Metcalf, “Quail Ranch Dropped,” Albuquerque Journal, July 26, 2007.

[26] KRQE staff, “City hires designer for Paseo del Norte expansion project,” KRQE, September 6, 2020. https://www.krqe.com/news/albuquerque-metro/city-hires-designer-for-paseo-del-norte-expansion-project/, last accessed 1/5/20.