A Special Report by The Red Nation on the final acts of the 23rdNavajo Nation Council

In the last week of the year, Navajo Nation Council (NNC) Speaker LoRenzo Bates scheduled a number of “special sessions” to consider the final resolutions of a departing council. The NNC scheduled and re-scheduled the consideration of one controversial issue in particular, Navajo Nation Council Resolution 0378-18, which asks the Secretary of Interior to organize the Navajo “Transitional” Energy Company, LLC (NTEC) into a for-profit corporationwith the latitude to “grow outside of the Navajo Nation.” Since its inception in 2013, NTEC has operated as a “limited liability” company wholly owned by the Navajo Nation. The first attempt by the Speaker to pass this resolution was a two-day meeting on the Thursday and Friday before Christmas (December 20 and 21). When this council failed to take up the resolution, Bates tried to bring it up again during yet another “special session” he organized. This was on Friday December 28. During the meeting, he was met by stiff opposition from Diné resisters who were opposed to the Navajo coal economy. Protestors waited all day for council to consider the resolution. Instead, delegates grew tired of debate and asked to recess until the following Monday – New Year’s Eve.[1]

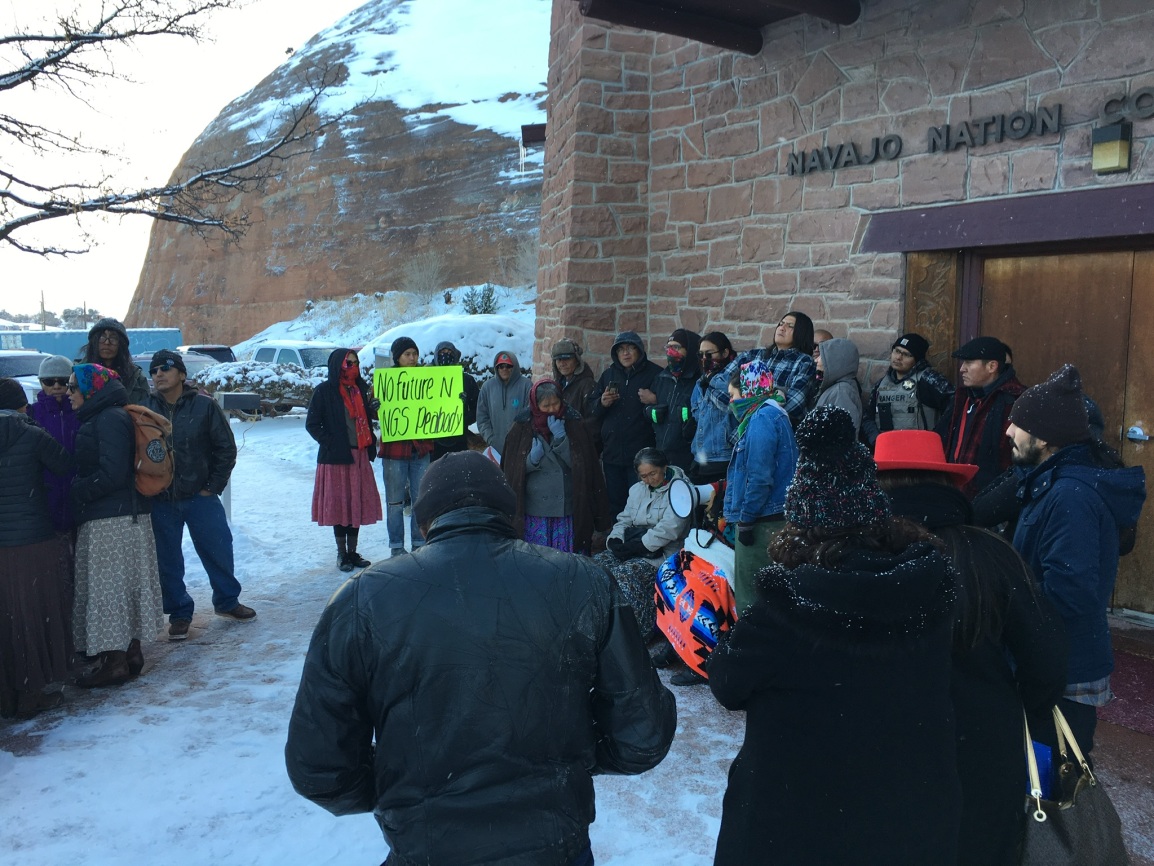

These were the final acts of the 23rdNNC. Many delegates, including Bates, will not return in 2019. Yet this outgoing council wants to saddle the Navajo Nation with the permanent legacy of coal. Diné resisters from Diné CARE, Black Mesa Water Coalition, Tó Nizhoni Ani, to members of the K’é Infoshop and The Red Nation protested outside of the council chambers on Friday, December 28. We recognized the proposed resolution as a necessary first step for NTEC to buy NGS and the Kayenta Mine from Peabody Coal, a costly and risky venture that all other energy producers are avoiding.

The Native face on front of a company makes it harder to see the insidiousness of colonization at work. In truth, NTEC is about rapacious capitalism and is the latest, ugly extension of neoliberal governance within the Navajo Nation. NTEC was born in crisis. It was a wishful attempt to salvage what is left of the Navajo coal economy in 2013. It remains a reflection of capitalist expressions of tribal sovereignty. Rather than protect us from colonial-capitalism, NTEC enhances it and makes it harder to dislodge in the future. Diné opponents mobilized against the bill 0378-18 as a threat against Diné lifeways. They see through the hairsplitting and disingenuous denials that NTEC has anything to do with the fate of the Navajo Generating Station (NGS). Diné people who have lived next to mines for generations and who have seen council after council make similar denials in the past recognize that the opposite will soon be reality. Nobody was fooled. Section 17 allows NTEC to avoid paying federal taxes and preventing victims of coal from suing the company because it is a creature of the Navajo Nation.

The end of the Gregorian calendar (not our calendar) is one of the few breaks during the year when we can stop working to spend time with relatives and family. It is purposefully undemocratic to schedule the deliberation of an important issue facing the Navajo Nation and Diné people when most tribal members lack knowledge of the proceedings and are otherwise unable to make it to the council chambers. For most protestors, the timing was also dangerous. Diné people who are resistant to the pro-fossil fuel agenda of the outgoing council had to brave icy BIA-administered roads in order to be there. Once they arrived to the council chambers, they discovered most of the seats were occupied by Navajo coal workers who were bused in by NTEC. Whereas the Navajo mineworkers were met by applause from the departing council, when they took their seats inside the council chambers, Diné water protectors were met by tribal police as they tried to voice opposition from outside in below freezing temperatures.

Tribal lawmakers were vague about the significance of Section 17 status for NTEC. On NTEC’s website, Section 17 is characterized as a way to extend the tribe’s “sovereign immunity” over any business activities NTEC might conduct. Sovereign immunity is a concept in U.S. law that prevents citizens from suing the federal or state governments. Tribal officials believe in notions of sovereign immunity and they argue tribes, like states and the federal government, are immune from lawsuit from their own citizens or citizens of other states. Section 17 of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (IRA) allows tribes to form corporations, which theoretically extends sovereign immunity over these entities. It is a dated mechanism that resurrects the paternalism of IRA in a desperate effort to absolve the Navajo Nation of any future liability in case the venture crashes and burns. Corporations organized under Section 17 are answerable to the Secretary of Interior and can only be disbanded by an act of Congress. Although the Navajo Nation rejected IRA in a referendum vote in 1934, most of its policies are considered applicable to the Navajo Nation. This includes Section 17 of the IRA. The very fact that we are appealing to provisions within IRA goes against the theory that we rejected it.

NTEC’s actions are consistent with buying the infrastructures of the NGS and Kayenta Mine from the Salt River Project and Peabody coal as they are slated to close at the end of next year, but tribal officials will deny this is what is happening. Almost five years to the day, in 2013 then Navajo Nation Attorney General Harrison Tsosie told the Navajo Nation Council that NTEC already enjoyed sovereign immunity as a freak creation of the tribe. NTEC subsequently hired him to serve as legal counsel. In 2013 the Navajo Nation Council was asked at the time to “waive sovereign immunity” in order to allow NTEC to enter into contracts with outside energy buyers. Now, on NTEC’s website, we learn, “in some cases, the Navajo Nation may be liable for company transactions.” They are acting like industry representatives, using the instruments of governance to exclude the Navajo public from the details of these transactions.

Navajo Transitional Energy Corporation as bottom feeder to the faltering coal industry

NTEC brands itself as an organization serving “the Navajo people.” Yet it is a private company benefiting from the precarious position of the Navajo Nation following decades of dependency on extractive industries. NTEC is a response that prevents the tribe from immediately dealing with the coal crisis. Although, NTEC owns Navajo Mine, it cannot operate it. It must contract with outside companies to keep the mine in operation. This was unanticipated when NTEC was created.

In summary, NTEC is a tax-exempt middleman in the Navajo coal economy with a Native face and white management. NTEC’s modus operandi is to borrow millions of dollars from banks and private lenders in the name of the Navajo Nation in order to buy mines and plants. In turn, NTEC subcontracts the actual operations of these parts of the coal-energy nexus while compensating themselves for the privilege of sitting in boardrooms and rubbing elbows with powerful industry types. However, coal is like the battery to an engine whose alternator has failed. The car will run for a time, but slowly profits will fade and the lights will dim. Already NTEC has brought the owners of the Four Corners Generating Stations, its sole customer, to “arbitration for reducing the amount of coal it buys from the company.”

In 2016, the previous owner of Navajo Mine, BHP Billiton, happily left and a subsidiary of North American Coal took over operations. This contract inevitably eats a substantial portion of the estimated $40 million in revenues NTEC earns from selling coal to the Four Corners Generating Station.[2]And as mentioned earlier, the owners of the power plant want to buy less coal from NTEC, from 5.2 million tons a year to 4.7. NTEC took the owners to “arbitration” to settle the matter, which was probably the only mechanism of recourse for the company according to terms in its lease. NTEC convinced the owners of Four Corners to make a onetime cash payment of $45 million to amend the 2016 lease and buy less coal for the duration of their lease that ends in 2041, assuming the Four Corners Generating Station will remain operational. This cash payout is fictional. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis claims that NTEC paid $145 million in total for its touted 7 percent share in Four Corners Generating Station. The owners of the Four Corners Generating Station didn’t give NTEC $45 million, but simply credited NTEC $45 million toward the $145 million costs for less than 10 percent of a fifty-four-year-old power plant on its last legs, making NTEC’s total payment to Arizona Public Service Company (APS) approximately $100 million.

In a neoliberal coal economy, the Navajo Nation no longer receives revenues from coal leases; it creates shadowy private companies (soon to be a Section 17 Corporation) to buy the discarded parts of the coal economy at tremendous costs and risks to the Navajo Nation and for millions of dollars in cash for large energy corporations. This is the formula that NTEC wants to follow in buying NGS. But NGS is even riskier. Fewer utilities wants to buy energy produced from the power plant. Not because they are suddenly environmentalist, but because it is more expensive than other sources. The challenge of buying NGS is fundamentally different for the Navajo Nation than buying Navajo Mine. For Navajo Mine, the tax-exempt status of NTEC allowed the company to bring the fuel-supply costs down to something APS and other utility-owners were willing to accept to continue operations. In that case, the fix was easier. At NGS, utility owners want to leave the power plant altogether. This is different. Not only will Navajo have to buy NGS and Kayenta Mine, it will also have to find a customer for the energy. No easy fix. Giving NTEC Section 17 Status allows the company to make these risky decisions with no formal accountability to the Navajo Nation. Rather, the Secretary of Interior, a Republican appointee for at least the next two years, will sign off on the conditions of the lease. It is 1984 all over again when the Navajo Nation negotiated a favorable lease rate with Peabody Coal only to have Regan’s Secretary of Interior James Watt reject it and force the Navajo Nation to negotiate for a lower rate after Watt held undisclosed talks with Peabody.

So who benefits? Energy corporations directly benefit. Cash goes into their hands, from NTEC, who must borrow millions of dollars to acquire more and more discarded parts of the declining coal economy. This behavior is not only risky for NTEC, and the Navajo Nation, but is also a perpetuation of colonial inequalities . Tribes take all the risks while energy corporations reap the profits. The management of NTEC is almost exclusively all White, while the workers are Native. Salaries, generated from the destruction of Native lands, goes directly into settler pockets. Money earned is likely to be spent at Wal-Marts in Farmington, NM—thereby funneling value from our lands and environments into the U.S. capitalist social order and bordertown economy. Tribal elites, who become NTEC board members or paid staff, also benefit. They are compensated handsomely, well beyond the average income of Navajo people. Because these staff are unelected officials, there is also no mechanism of accountability or anyway to ensure that NTEC employees don’t take profit from Navajo Mine all for themselves. This is the danger of corporate governance for tribes. And this is the direction the Navajo Nation wants to move.

Toward a permanent homeland for the Diné people

NTEC is zombie neoliberalism, where dead capital infrastructure comes back to life to eat on the living. A NTEC-run Kayenta Mine will undoubtedly transform the Navajo Coal economy. A zombie needs bodies on which to feed and in colonial-capitalist relations, the bodies are measured in profit. Broken bodies and environmental contamination are converted into dollar bills with the portrait of the very white men who worked tirelessly to eliminate Native life from the land. Aside from taxes, labor is another variable likely to lose out in a future NTEC-NGS partnership. To run “efficiently,” NTEC will have to cut labor costs, first by laying off workers and then reducing their benefits while paying themselves handsomely as managers of this new social realty. Likely, we will see the face of tribal officials who are currently deciding on this legislation reappear as board members or future employees of the company, a small reward for doing the company’s bidding. In the end, the professed goals of keeping coal-working families intact will be quickly cast aside to keep NTEC profitable. The land, water, and air we need in order to survive and sustain a “permanent homeland,” in the words of Diné coal resisters, will be forever sacrificed for a world in which the few, industry-connected Navajo officials dressed in suits live high in bordertowns while the rest of us are told to pull ourselves up by our moccasin straps. We must stand up and resist this corporate takeover of Diné life and the continuation of colonial extraction across Diné homelands. More importantly, we need to sustain lifeways that lead us out of colonial-capitalist structures. In the spirit and actions of the Black Mesa matriarch, we must confront any structures that threaten our lifeways. As one protester said, “I know the good way to do it. I know how Martin Luther King did it, I know how Malcolm X did it. That’s the good way. The good way is not to sit and down and be quiet and go outside”.

NOTES

[1]Not to reify the sentiment of these colonial holidays, but it is to recognize that working people are especially busy during this time of year. As one Diné resister put it, “some of us have livestock we have to get back to.” They volunteered their time to come out to council chambers and protest a reality being structured around them without their input. When a police officer responded, “if you don’t like it, vote for someone else,” he didn’t realize that many of these people were active in Navajo politics and have pleaded to their delegates only to be ignored, turned away, or placated with vague promises of future action. Many of these people came from Black Mesa and their delegate, Dwight Witherspoon, gave up on them. Resigning to be chief-of-staff for the outgoing Russell Begaye. How could they claim representation in this forum under these conditions? The political reality in Navajo as it is in the United States is that money speaks. White men in suits have more money than saanis living on the land. Witherspoon only speaks English. Bates only speaks English. English is the language of capitalism. How are Diné speaking saanis living on the land supposed to be heard in these colonial conditions?

[2]In their annual report to shareholders, The North American Coal Corporation bragged about its acquisition of the lucrative Navajo Mine contract, begging January 1, 2017. The corporation made $37 million before taxes after taking over Navajo Mine from under $1 million the previous year (page 3 of the report). Obviously other factors were at play, but the increase is noticeable.

Subscribe: