By Andrew Curley

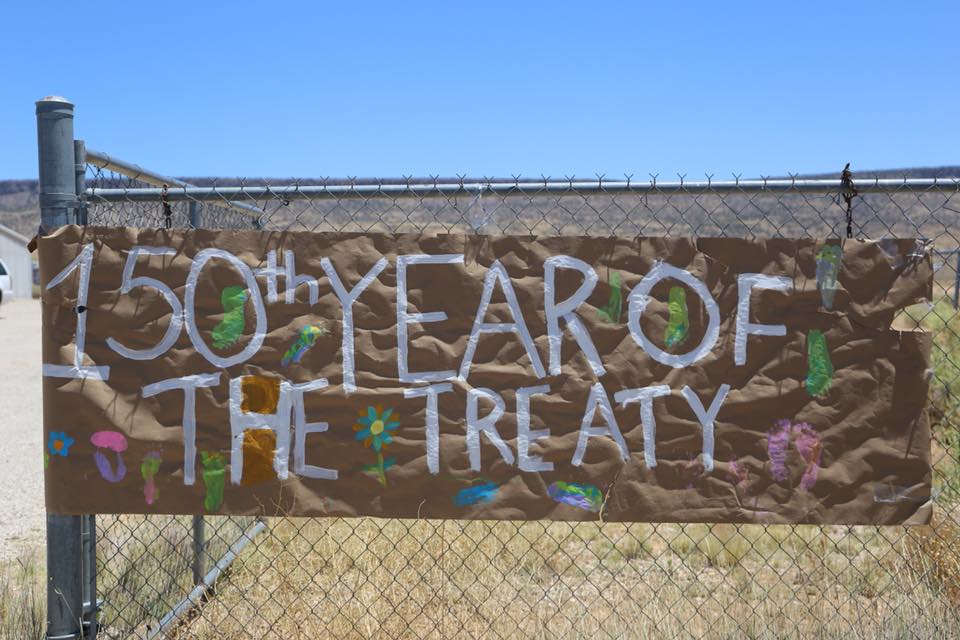

Today we commemorate the 150th anniversary of the treaty between the United States and “the Navajo band of Indians.” Most Navajo people are unaware or unconcerned about this date and its supposed significance. Tribal officials, on the other hand, are planning celebrations and events across the reservation. But what should we make of this date?

To me, it is not a date of celebration. It is a reminder of our continued colonization and lack of independence as a nation and a people. The treaty signifies the termination of our internment at Bosque Redondo, a concentration camp where our ancestors were forced to live at the end of a bayonet.

But Hwéeldi never ended. Our ancestors were allowed to return home only under duress. Barboncito and other “headmen” agreed to strange and obscure conditions prepared by U.S. General Sherman and his staff that reflected the prioritizes of a settler-colonial state, not the Diné people.

Articles of the treaty that we supposedly “agreed” to were the enforcement of U.S. punitive jurisprudence over our people, guarantees not to disrupt a booming rail industry, assimilation through boarding schools, and a reduced homeland that did not include most of central, western, or eastern agencies today.

This was not so much a “treaty” between nations as it was conditions of parole for the crime of being Indian – conditions that could trigger military reprisals at any time. The treaty was born in death, destruction, and violence and should not be an object of celebration or fetish. Today, the treaty demarcates an implied line between White and Native citizenship that prioritizes the former at our expense.

Bordertowns are sites of colonization that penalize Native presence. The police have replaced the military and today our people are confined in jails and prisons throughout the towns and cities built along the railways we supposedly agreed not to disrupt. Our best range lands were distributed to white settlers, who dammed and diverted the regions surface waters, such as the Little Colorado River, at our expense.

Hwéeldi continues today. We are forced to work outside of the reservation for survival, we are targeted and harassed by city and state police around the reservation and our homelands are denied water rights while climate change intensifies. We are not prospering in the U.S., which should force more introspection than celebration.

The treaty did not protect us but facilitated many of these processes. It also enfranchised men over women and undermined other traditional forms of leadership. The Treaty of 1868 was the transformative event to social, cultural, and political changes we are desperately struggling to overcome today. It is when traditional knowledge slipped, when language started to decline, and when strongmen replaced headmen and women to monopolize power within the reservation system.

Not included in our treaty were rights to water, which is our most pressing issue today. Although Diné people have lived in the region since time immemorial, our “priority dates” are pegged to arbitrary years when the U.S. government recognized us. The expansion of the Navajo reservation did not happen at once or uniformly. And although Navajo people have been living along the Little Colorado River since Europeans toiled in dirt and mud for feudal lords, our rights have become secondary to Mormon settlements upstream – adherents to a religion invented in the 19th century.

Some Navajo people will read this as extremist rhetoric and out of touch with the lived realities of the reservation. Many Navajo people today take pride in their U.S. citizenship because they feel it grants them “freedoms.” But the United States did not emancipate us. This is propaganda taught in grade schools or in military boot camps. The truth is that we enjoyed more personal and political freedoms prior to colonization. The bars on the U.S. flag might as well represent the number of signatures required between tribal, state, and federal institutions to get a project underway in the reservation.

We must reject the restrictions on us inherent in the Treaty of 1868 and strive for a presence in the region that transgress state and national boundaries, borders and walls. We have to plan our future beyond the United States, both physically and temporally. We need to secure water, life, livelihood, and welfare within our nation and between us and our neighbors. This does not mean abandoning institutions, industry, or other markers of modernity. But it does mean scaling back how much we consume and how much impact we have on the planet. Let us make a new treaty, among ourselves, to build a prosperous and sustainable future on and within our historic homeland.

Subscribe: