December 26, 2018

Dear friends,

Greetings from The Red Nation. (Subscribe to our newsletters here.)

’Tis the season of giving. We need Red Santas to support our work!

If you enjoy our newsletters, articles, teach-ins, reading groups, conferences, events, or just like the work we do, consider donating! Sign up for a monthly contribution. Every dollar goes towards new and developing projects, such as: holding community water talks and teach-ins to battle the oil and gas industry; producing our forthcoming Red Revolution Radio podcast; writing, researching, and advocating anti-colonial and anti-capitalist transition policies; collecting winter and survival gear for our relatives on the streets; hosting the 2019 Native Liberation Conference; and renting a larger, more accessible office space for meetings and study groups, as we expand and grow. (Donate here.)

If you’ve already donated. Thank you!

This time of year many Indigenous nations observe the winter solstice, a time for deep reflection and storytelling. Winters were especially hard, but they were also times of transformation. Although short, days grew longer. Temperatures dropped. Animals hibernated. Winds stung. We gathered inside seeking the warmth of loved ones and fortifying ourselves with stories, meals, and ceremony. In the North, an individual’s life was once counted by the number of winters they had survived. Today, it is a holiday season, a time also shared with friends and family. (Listen to the While Indigenous podcast on “Decolonizing Holidays” here.)

For Indigenous peoples, December is also marked by horror—a time when worlds violently ended.

In this newsletter we turn to the North, to honor our Oceti Sakowin relatives, the Dakota-, Nakota-, and Lakota-speaking peoples and the nightmares they’ve faced. Kiksuyapo! Remember!

Dakotas know their homelands as Mni Sota Makoce, Land Where Water Reflects the Clouds (what is currently Minnesota), a place that cares for the relatives who care for it. It was the late summer of 1862, a time normally celebrated with bountiful hunts and harvests. That summer, there was almost nothing. Decades of white European invasion had scarred the land, introducing foreign agriculture that nearly exterminated native agriculture, such as wild rice and cornfields, and animals, such as the buffalo and deer—the survival foods for Natives of the western woodlands of Lake Superior.

In 1851, Dakota men—under coercion and without the authority to do so—had signed away all their nation’s lands except for a narrow twenty-mile strip. This greatly diminished their nation’s ability to hunt, gather, and grow food. After gaining statehood in 1854, white Minnesota settlers aimed to expel the remaining Dakotas through fraud, deceit, and starvation. During the Civil War, treaty rations arrived too late or not at all. Indian agents and white traders had swindled the starving Dakotas. “Let them eat grass,” said Andrew Myrick, a notorious trader who withheld treaty provisions from hungry Dakotas who had accrued debts with him.

The Dakotas faced an existential dilemma: fight or die. With nowhere left to hunt or harvest, there was nowhere left to live and nowhere left to run. Backed into a corner, the only option left was to repel the invaders.

In August 1862, under the leadership of Taoyate Duta (He Loves His Red Nation)—known to whites as Little Crow—the Dakotas moved against the settlers, killing 800 of them within thirty-seven days. Among the dead, Myrick, the cruel white trader, was found facedown in the dirt with grass stuffed in his mouth. He was killed while running away.

Settlers quickly mobilized vigilante militias and organized the first Minnesota National Guard to kill Indians and secure a white future on the land. By September, most of the Dakota resisters had surrendered. By November, a military tribunal tried 392 Dakotas for “murder and outrages,” convicting 323 and sentencing 303 to death. Soldiers imprisoned more than 2,000 at Fort Snelling in a large, open-air concentration camp, where many perished. President Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, commuted most of the death sentences, except for thirty-eight Dakota men and boys.

On December 26, 1862, the day after Christmas and a week before signing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln ordered the hanging of thirty-eight Dakota patriots. Soldiers confiscated their medicine bundles, heaped them in a pile, and burned them. They sang their death songs as they were led to the gallows. It remains the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

Minnesota issued scalp bounties encouraging settlers to take their own vengeance and to exterminate the remaining Dakotas. A white farmer murdered Little Crow, the leader of the uprising. After scalping and decapitating him, settlers placed Little Crow’s body on display at the Minnesota Historical Society. The state also organized “columns of vengeance” to track, capture, and kill the fleeing Dakotas. On September 3, 1863, at Whitestone Hill in what is currently North Dakota, soldiers attacked a Dakota buffalo hunt, massacring hundreds of children, men, and women and taking hundreds more captive. (Read LaDonna Brave Bull Allard’s history of the massacre here.)

West of the Missouri River, the Lakotas called the invaders Milahaskan, the Long Knives, because they had come to know settlers best through their military, which wielded swords. The Lakotas knew the U.S. as a predator nation.

For decades, the Lakotas had, for the most part, kept white encroachment at bay. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty had reserved more than 70 million acres of territory for the Lakotas’ exclusive use. With the treaty, two things sustained their resistance: the buffalo and He Sapa, the Black Hills, the heart of everything that is.

By 1873, that changed. Gold was discovered in the Black Hills. In a desperate and stupid endeavor to take the hills, in 1876 Colonel George Armstrong Custer attempted to crush a Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho alliance. Instead, Custer and 268 of his men were wiped out at the Battle of Greasy Grass. With a military defeat now impossible, the Army targeted the Lakotas’ closest relative and primary food source, the Pte Oyate, Buffalo Nation.

Within two decades, the Army slaughtered the remaining 10-15 million buffalos. The tactic was effective. Slowly, the militant factions began trickling into assigned reservations searching for food. The children of leadership were taken and sent to government-run boarding schools as hostages to control the behavior of their people. The 1877 Black Hills Act swindled the Black Hills from the Lakota, thus abrogating the 1868 Treaty.

By 1889, when South Dakota gained statehood, the Lakotas were horseless, unarmed, starving, and confined to reservations. The great Lakota resistance leader, Tasunka Witko (Crazy Horse), had been assasinated in 1877. However harmless Lakotas may have been, they represented the final barrier to white settlement because they controlled nearly the entire western half of the state. That threat, real or imagined, came to life in 1890 with the Ghost Dance.

The Ghost Dance swept the Northern Plains like prairie fire. Its prophet, Wovoka, a Paiute holy man, had envisioned a cleansing that would wipe the United States off the map and restore the Indigenous world, a world premised on solidarity, peace, and justice. Tatanka Ptecela (Short Bull) relayed Wovoka’s vision to Luther Standing Bear at the Rosebud Agency: “He told us we were to have a new earth; that the old earth would be covered up… that all the white people would be covered up, because they did not believe.”

To Lakotas, the message rang especially true. Civilization regulations banned dancing and all forms of Indigenous ceremony not sanctioned by the church. In other words, to dance was to break the law. Therefore, the Ghost Dance was illegal. The United States made the Ghost Dancers criminals to hide its own criminal behavior; so it deployed half its standing Army to crush starving, unarmed people. But you cannot kill or imprison revolutionary ideas and movements. After all, the Ghost Dance arose in direct response to the violent reservation system, the stealing of children, and the continued theft of lands.

Tatanka Iyotake (Sitting Bull) became the first target. A long time resister of allotment and the reservation system, he hosted Ghost Dancers at his camp at the Standing Rock Agency. This gave the Indian agent, James McGlaughlin, and the Indian police reason to arrest him. On the morning of December 15, 1890, two Indian police, Bullhead and Red Tomahawk, shot Sitting Bull dead.

After Sitting Bull’s assassination, the Ghost Dancers fled, led by Hehaka Gleska (Spotted Elk), known to whites as Big Foot. Hungry, sick, unarmed, and horseless, they traveled hundreds of miles to Red Cloud Agency seeking sanctuary. There, they were surrounded and detained by Custer’s old regiment, the Seventh Calvary. On the morning of December 29, soldiers began confiscating weapons, such as hatchets and knives. A shot was fired. In several hours, the soldiers killed about 300 Ghost Dancers, including Spotted Elk himself. Two-thirds of the slain were women and children. “Remember Custer,” the soldiers said under their breath as they delivered finishing blows.

While tragic, the Ghost Dance didn’t end at Wounded Knee. “The tree that was to bloom just faded away,” the holy man, Nicolas Black Elk, said of the prophecy, “but the roots will stay alive, and we are here to make that tree bloom.”

Indeed, the tree of life bloomed at Wounded Knee in 1973 and at Standing Rock in 2016. The long traditions of Indigenous resistance have kept us alive. To begin this process of seeking justice is to remember. Kiksuyapo.

The Dakota 38 Riders trek from Lower Brule, South Dakota to Mankato, Minnesota each year to remember their Dakota ancestors. (Watch the documentary “Dakota 38” here.) Around the same time, the Big Foot Riders travel from McGlaughlin, South Dakota to Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota to remember the Ghost Dancers, to help the tree of life bloom again. Because they know another world is possible. That’s the Ghost Dance Prophecy.

In this part of the world, from where I write in New Mexico, the Pueblo and Diné people are reawakening. On December 5, Indigenous women led a protest against Trump’s colonial land grab and the selling off of Indigenous lands to the oil and gas industry. It was a historic event, a step towards militant Indigenous-led resistance against the fossil fuel industry in the state. As the First Peoples of this continent, we reject the idea of “public lands” when those lands were stolen from Indigenous peoples in the first place. And we want them back. Justine Teba, a powerful voice from the Tesuque Pueblo and a The Red Nation member, writes, “We will not compromise on our future, on our relations, and on our future relations.” (You can read her full report here.)

And we know that the Long Knives (the United States) have committed, and continue to commit, many Wounded Knee massacres. In Yemen, war targets the young. A recent report found that in the last three years of civil war 85,000 Yemeni children starved to death as part of the U.S.-backed Saudi-led war. Before shutting down the government in response to funding for Trump’s border wall, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution to end U.S. support for the Saudi war in Yemen. We hope peace in Yemen is on the horizon.

And before the Senate convened a hearing on Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women on December 12, a seven-year-old Indigenous girl named Jakelin Caal, who was Q’echi’ Mayan, died in the custody of U.S. Customs and Border Patrol the week before. According to her father, Jakelin was in good health when she was taken into custody. Whatever the circumstances, we must count ALL Indigenous women and girls killed at the hands of the settler state, and we must humanize them, not in death, but in life by tearing down imperial borders and treating them with dignity as relatives. Jakelin’s death was preventable, as are the countless who have died because of the cruelty of borders and police.

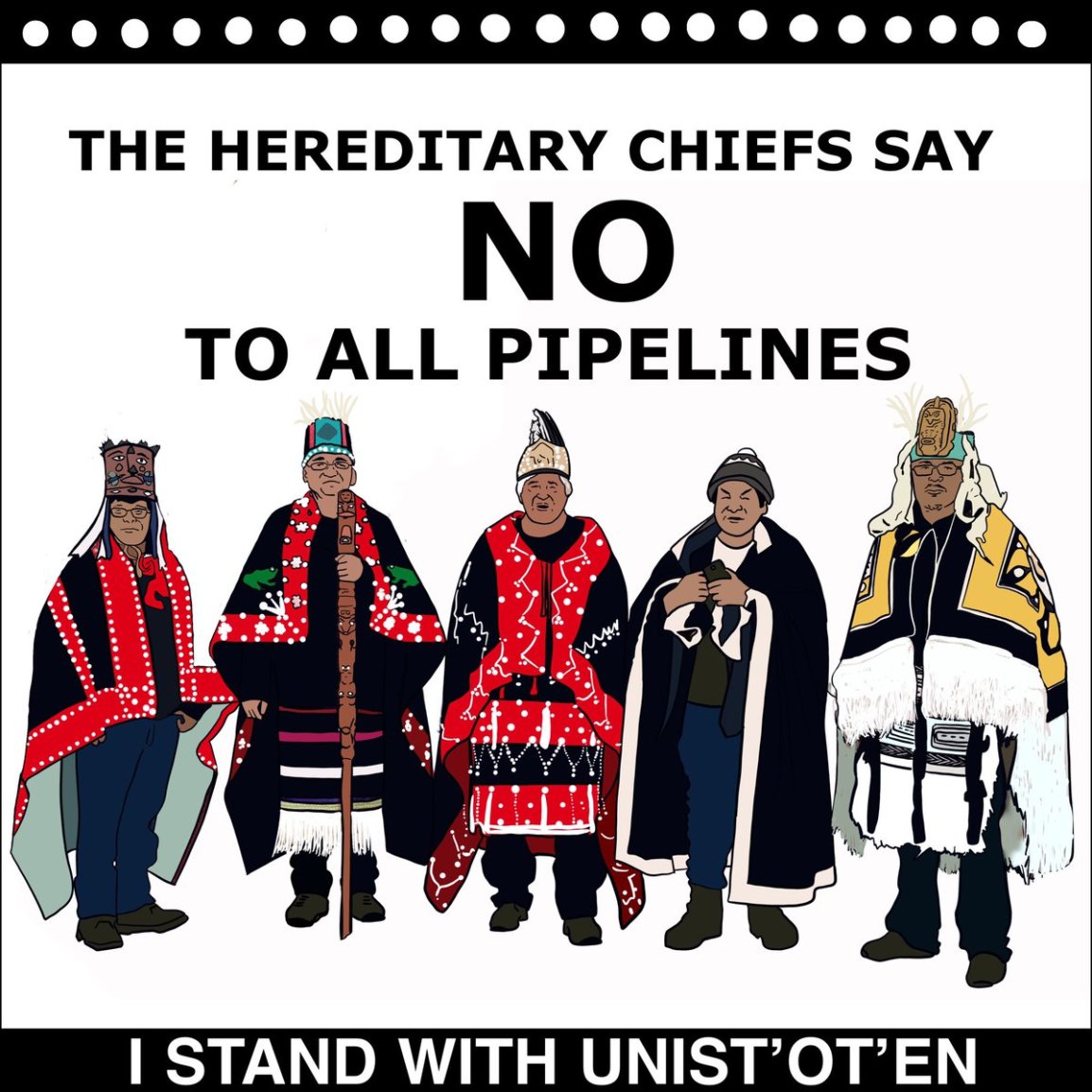

In the North, the Canadian settler state wages war against Indigenous nations to protect the profits of big oil. The Wet’suwet’en nation has never signed a treaty with or ever ceded land to Canada. Yet, their territory is occupied. Last week, a British Columbia judge issued an injunction to allow Coastal GasLink to build an oil pipeline through unceded Wet’suwet’en territory. But a blockade of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples prevented Crown authorities from issuing the order. The injunction targets Unistot’en Camp, which has prevented pipeline construction for the last eight years. Karla Tait and Anne Spice, friends of The Red Nation, wrote this beautiful rebuke of the illegal settler state’s incursion:

These companies are skirting the legitimate and recognized decision makers of the Wet’suwet’en Nation in order to access the territory without consent, and they are likely to leverage the RCMP [Royal Canadian Mounted Police] to enforce their trespass. This must not be tolerated. What part of NO do they not understand?

Please support our Wet’suwet’en relatives, who are on the frontlines. (Here is their call for solidarity.)

Water Protectors are also mobilized against the Bayou Bridge Pipeline in Louisiana (support L’Eau Est La Vie Camp here) and against Line 3 in Minnesota (support that struggle here). This season, remember all our frontline warriors who are fighting for our land and water, for our right to live. Thank them by supporting them.

As Indigenous peoples, we remember what it is like to lose our worlds and our relatives. We will not let that happen again. We also know that the history and future of this land will always be Indigenous. Kiksuyapo!

Solidarity forever,

Nick

Subscribe: